|

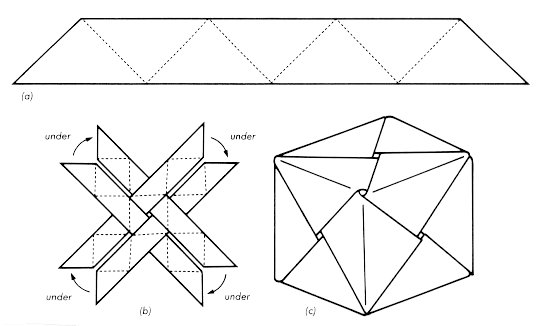

Figure 5: (a) Left-hand end of pattern piece;

(b) Pentagonal dipyramid; (c) Triangular dipyramid.

|

Figure 5(a) shows the left-hand end of the 31-triangle strip used to

construct the pentagonal dipyramid (with the colored side up). You should

mark the first and eighth triangles exactly as shown (note the orientation of

each of the letters within their respective triangles). To assemble the

model place the first triangle over the eighth triangle so that the circled

letters A, B, C are over the uncircled letters

A, B, C, respectively. Holding those

two triangles together in that position, you

will notice that you have the frame of a double pyramid for which there will

be five triangles above and five triangles below the horizontal plane of

symmetry (the plane containing the vertices 1, 2, 3, 4, 5 in

Figure 5(b)). Now hold this configuration up and turn it so that the long

strip of triangles falls around this frame. If the creases are folded well,

the remaining triangles will fall into place. When you get to the last

triangle there will be a crossing of a strip that the last triangle can tuck

into, and your model will be complete and stable.

If you have trouble because the strip doesn't fall into place there are two

frequent explanations. The first (and most likely) reason is that you have

not folded the crease lines firmly enough. In that case all you need to do

is crease them again with more gusto! The second possible reason is that

the strip seems too short to reach around the model and tuck in. This may

be remedied by trimming a tiny amount from each edge of the strip.

An analogous construction may be made for the triangular dipyramid shown in

Figure 5(c). This model can be made from a strip of 19 equilateral

triangles. Knowing what the finished model should look like and that you

should begin by forming the top three faces with one end of the strip should

be sufficient hints.

You may discover that you can construct each of these dipyramids with fewer

triangles, but we chose the construction that produces the most balanced

model. You will note that both of these constructions place precisely three

thicknesses of paper on each face, except where the last triangle tucks in

(producing four thicknesses). In both cases, you could remedy this small

defect by cutting off half of the first and last triangle on the strip.

Now let us turn to the Platonic Puzzles.

|

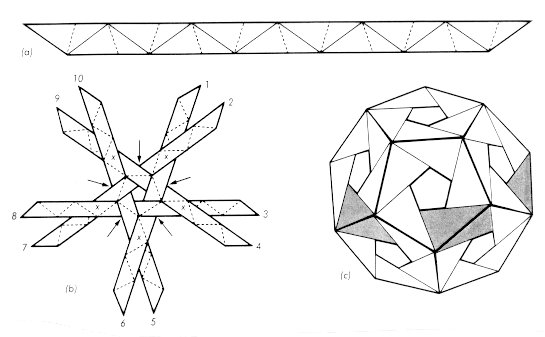

Figure 6: 1) Tetrahedron (2 strips); 2) Hexahedron (Cube) (3 strips);

3) Octahedron (4 strips); 4) Icosahedron (5 strips);

5) Dodecahedron (6 strips, 3 of each kind).

|

Figure 6 shows a typical puzzle piece (or strip) next to each solid, and

tells you how many are needed. In each case the puzzle is this: take the

required strips and braid them together to from the required solid in such a

manner that

(a) the same area is visible on each strip, and

(b) all ends are tucked in.

The tetrahedron, octahedron, and icosahedron all involve strips obtained

from the D1U1-folding procedure.

All you need to do is prepare the

pattern pieces as we described above and try to assemble the models. You

may note that, on all of these models, if you take into account the coloring

of the surface, they will have lost some of the symmetry you would expect to

find on Platonic Solids; that is, not all edges will look the same. For

some edges the two adjacent faces will have the same color but, for other

edges, the two adjacent faces will have different colors. (We will propose

another type of construction that corrects this defect in

Section 5). If

you manage to get all three of these together without any hints you are

really an expert! If you have trouble getting your models together check

the hints given in Section 4.

The hexahedron (cube) pattern pieces may be made by making exact folds on the

tape. All that you need to remember is that if you fold the tape directly

back on itself you will produce an angle of precisely p/2,

and if you bisect that angle you will know exactly where to fold the tape

back on itself to produce a square. Once you have one square on the tape

you may then simply fold the tape back and forth, accordion style, on top of

this square to produce the required number of squares. There are actually

two ways to braid these three pieces together to satisfy the conditions for

the puzzle. One of these ways produces a cube with opposite faces the same

color and the other way produces a cube with certain pairs of adjacent faces

the same color. From the point of view of symmetry the first is more

symmetric because, on that model, all edges abut two faces of different

colors. If you have trouble assembling this model check the hints given

in Section 4.

The dodecahedron involves strips obtained from the

D2U2-folding

procedure. But notice on the final pattern piece you should only fold the

pattern piece firmly along the short crease lines (ignoring the long lines)

after you have cut out each piece. We should tell you that on this model

four sections of each strip will overlap (for stability). It may also be

helpful to let you know that the strips go together in pairs and the

construction is then similar to that of the more symmetric cube you have

constructed above - and, if coloring is taken into account, the completed

model loses a lot of the symmetry you expect to see on a dodecahedron. You

may now have enough hints, but if you have difficulty consult

Section 4.

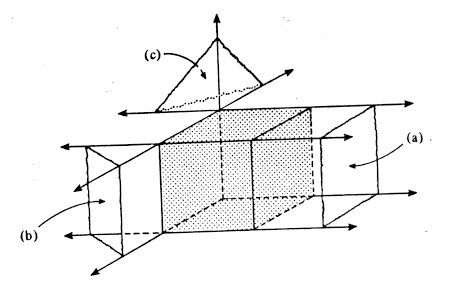

The diagonal cube involves four strips each containing 7 right isosceles

triangles as shown in Figure 7(a). The strips for these pieces may be

folded by the exact procedure similar to that described above for the cube in

the Platonic Puzzles. Just remember that this time you want to emphasize

those crease lines that make an angle of p/4 with the edges

of the tape. To assemble the cube you begin by laying out the four pieces

as shown in Figure 7(b), with the colored side of the paper not showing.

You may wish to put a small piece of tape in the exact center to hold the

strips in position. Now, thinking of the dotted square surrounding the

center as the base of your cube, you begin to braid the strips to make the

vertical faces, remembering that each strip should go successively over and

under the strips it meets as it goes around the model. When you get to the

top face you will find that all the ends will tuck in to produce a very

beautiful and highly symmetric cube; indeed, none of the symmetry of the cube

has been lost. You will notice that every face has a different arrangement

of four colors and that every vertex is surrounded by a different arrangement

of three colors.

Figure 7

The golden dodecahedron involves strips obtained from the

D2U2-folding

procedure. But notice on the pattern pieces you should only fold the

pattern piece firmly along the long crease lines (ignoring the short lines)

after you have cut out each piece. To complete the construction of this

model, begin by taking five of the strips and arranging them, with the colors

showing, as shown in Figure 8(b),

securing them with paper clips at the

points marked with arrows. View the center of the configuration as the

North Pole. Lift this arrangement and slide the even-numbered ends

clockwise over the odd numbered ends to form the five edges coming south from

the arctic pentagon. Secure the strips with paper clips at the points

indicated by crosses. Now weave in the sixth (equatorial) strip, shown

shaded in Figure 8(c), and

continue braiding and clipping, where necessary,

until the ends of the first five strips are tucked in securely around the

South Pole. Above all, keep calm, you can even take a break - the model

will wait for you! Just make certain that every strip goes alternately over

and under each strip it meets all the way around the model. When the model

is complete (with the last ends tucked in) you may remove all the paper clips

and the model will remain stable. We notice that this constructed

dodecahedron is aesthetically very satisfying - more so than the

dodecahedron previously described. This is due to its amazing symmetry -

none of the possible symmetry has been lost.

Figure 8

Before giving you the hints for the remaining models we cannot resist showing

you a lovely use for the cube with three strips, the diagonal cube and the

golden dodecahedron. An interesting question5

that has been asked by geometers (see [KW]) is "How many

disjoint pieces - both finite and infinite (or unbounded) - are formed

by the extended face planes6

for each Platonic solid?" As it turns out we can use our braided

models to answer some of these questions in the case of the unbounded

regions.

Let us use the ordinary cube to show how the braided models are useful.

Notice that the edges of the three strips used to create the braided model

lie in 6 planes which interesect each other to form a cube. Figure 9,

suitably interpreted, shows that the extended face planes of a cube partition

space into 27 pieces. There is, of course, the cube itself, which is

bounded. Then come the unbounded regions. There are

(a) 6 unbounded square prisms from its faces,

(b) 12 unbounded wedges from its edges and

(c) 8 unbounded trihedral regions from its vertices.

Now if you examine your braided cube you will see that there are

(a) 6 square regions that are covered with precisely two thicknesses of paper,

(b) 12 small slits along the edges where there is just one thickness of paper and

(c) 8 tiny triangular holes at the vertices.

This observation gives us the clue

as to how braided models may be useful more generally in answering our

question.

|

Figure 9: Using the braided cube to count the unbounded regions created

by the extended face planes of the cube.

|

What turns out to be true is that the braided models partition the surface of

the polyhedron into mutually disjoint sets of 'polygons' where each polygon

is covered by 0, 1 or 2 thicknesses of paper. The polygons where

there are holes (0-thickness) define unbounded polyhedral regions, the

polygons which are narrow slits (1-thickness) define unbounded wedges, and

the polygons where the strips actually are crossing each other (2

thicknesses) define unbounded prisms. The shapes of these unbounded regions

may vary with the braided model, but these general statements always hold.

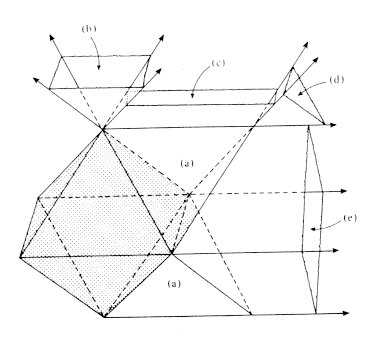

If we are to be able to answer our question for the octahedron we need a

braided model with 4 strips so that their edges will define 8 face

planes - and, of course, the braided model should also have the same

symmetry group as the octahedron. Fortunately the diagonal cube satisfies

our conditions (see [Math] concerning the duality of the cube

and octahedron). Figure 10 shows the octahedron with

some of its face

planes extended so that you can see a typical finite region and typical

unbounded regions of each type. The braided models don't help to count the

bounded regions (in this case, however, we can see from the part of

Figure 10

labeled (a) that there is a tetrahedron on each face of the original

octahedron). The rest of the labels in Figure 10

indicate unbounded regions

and Figure 11 reproduces

those regions as they are associated with the

surface of the diagonal cube. Thus, using Figure 11,

we may now count the

unbounded regions. They are (using the labels in Figure 11):

(b) 6 unbounded tetrahedral regions from the holes in the center of the faces,

(c) 24 unbounded wedges from the 4 slits on each of the 6 faces,

(d) 8 unbounded trihedral regions from the vertices,

(e) 12 unbounded, prism-like regions from the crossings of the

strips on the edges

comprising a total of 50 unbounded regions.

|

Figure 10: Extending the face planes of an octahedron.

|

So the golden dodecahedron must also be useful. In fact it is composed of

six strips and the planes defined by the edges of those strips intersect

inside this model to form a dodecahedron. Thus the surface of the golden

dodecahedron can be used to see that there are 122 unbounded regions created

by the extended face planes of the dodecahedron. You might like to try to

count them yourself using your golden dodecahedron (or see [P]

for more details).

What about the icosahedron? Figure 11 shows

how a model, braided from 10 straight strips, may be made from the

D2U2-tape that can be used to

count the 362 unbounded regions created by the extended face planes of

the icosahedron (see [P] for more details). We have not

written down anywhere how to make the model shown in Figure 11,

but we're sure the interested reader will be able to figure it out from what we have

said and the illustration.

You may be asking yourself why we have slighted the

tetrahedron. The answer is that the tetrahedron does not have faces lying

in opposite parallel planes, so our models are not useful here. However, it

is not difficult to imagine extending the face planes of the tetrahedron and

seeing that you have one finite region (the tetrahedron) and 14 unbounded

regions (4 from vertices, 6 from edges and 4 from faces).